The Median Problem

This week I learnt the hard way that startup advice is a set of heuristics that work for the median company. But the most interesting companies are rarely the median.

I was at this startup workshop listening to a VC explain why founders fail. Everyone around me was furiously taking notes about finding PMF, co-founders, complementary skills, the whole playbook. Most people around me seem to be building either developer tools or another direct-to-consumer brand, hoping to cash in on the Indian customer story that has been “under maturation” for a decade now. I’ve been guilty of advancing that narrative myself while at Flipkart.

It feels like we’re all following a playbook, but ignoring the most important question: what are we uniquely suited to build?

Note to Self: I Am a Hacker

My own answer comes from a lifetime of being a hacker. Not just the coding kind, but the kind who takes things apart to see how they work.

Growing up, I always called myself this. I started by taking apart code, trying to understand the logic of systems others had built. Then I moved on to music software, video editing tools, and marketing platforms. The pattern was always the same: deconstruct something to its core components, then reassemble it to see what else it could do.

What I discovered was that most tools aren’t built for the work itself. They are built to enforce a process. They have their own rigid ideas about how you should think, and the cost of using them is that you must bend your brain to fit their structure.

The Quiet Friction

For years, I lived with this quiet friction, this tax on creativity.

When I ended up in product marketing, it felt like all these random interests finally made sense. I was the person translating between the engineers who built the product and the marketers who had to sell it, and I saw how the tools we used failed both of them. They created a chasm between a good idea and its execution.

I’d spend hours trying to explain why a product mattered, fighting with templates and frameworks that missed the point entirely. The creative process got buried under layers of corporate process. It was a problem I couldn’t stop seeing.

The AI Thing…

When recent developments in AI became powerful enough, I realized a new type of tool was possible. One that didn’t impose a framework but adapted to the user. A tool that could act as a collaborator, not a container.

I quit my job to build it.

Rhea asked me the other day what I truly love and want to do for the rest of my life. I vaguely said something about media and tech. But this makes sense. This actually makes sense.

Too Personal to Share

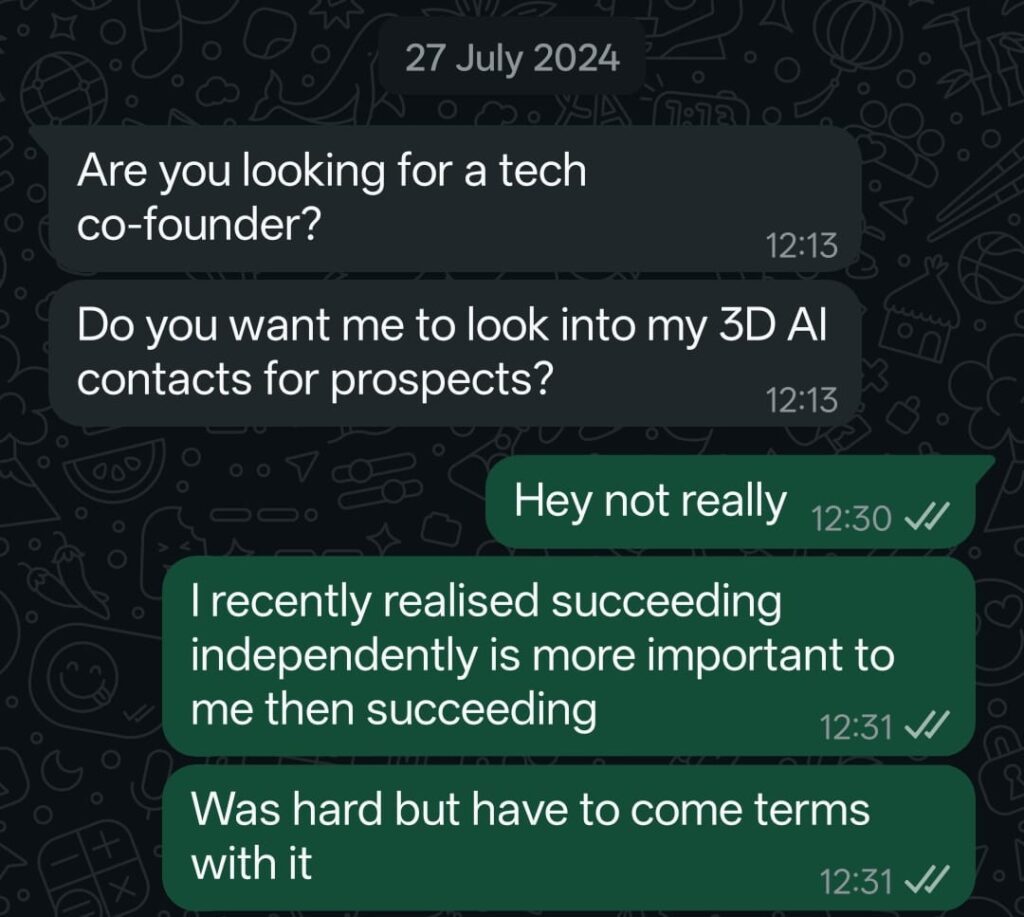

People keep asking the median questions about co-founders and market size. The truth is, this thing I’m building is too personal to share right now.

It’s the direct result of a specific obsession, and in these early stages, the greatest risk isn’t a lack of resources—it’s the dilution of that core idea. When you’re building something that feels like an extension of yourself, finding someone who shares your specific lens becomes exponentially harder. You need someone who feels the same visceral connection to the problem you’re solving.

A singular, uncompromising vision isn’t a bug; it’s the entire feature.

The Only Playbook That Matters

Perhaps the only playbook that matters is to solve your own problem. You can’t get closer to a user than by being the user. You build, you use, you fix. The feedback loop is instantaneous.

Maybe I won’t build the next unicorn. Maybe Vinci will stay small and weird and only make sense to people like me. That’s okay. I’m not optimizing for venture scale or following some playbook about market size and go-to-market strategy.

You’re not trying to prove anything to investors or follow a trend. You’re just trying to bring something into the world that feels true.

I spent so many years trying to fit into other people’s definitions of what a career should look like, what success should look like, what building a company should look like. The workshop guy with his co-founder rules was just another version of that.

But here’s what I’ve learned: being a misfit isn’t a problem to solve. Sometimes it’s exactly what the thing you’re building needs.

The misfit part isn’t a bug. It’s the whole point.